In spite of the really foul wet and windy weather, I decided to brave the elements and brew a beer over the leap year weekend – after all, I did have an ‘extra’ day in the year to do it!

English Ales are all very well, but once in a while it’s nice to brew something different, so I decided to brew a Belgian Witbier. To make the brewery day slightly easier I used my Braumeister 50L (BM) one-pot brewing system – less equipment to wash up at the end of the day!

INTRODUCTION TO WITBIER & ITS ORIGINS

Belgian white beer (or Witbier) has a unique cloudy-white appearance with very little bitterness, some spiciness, and a slightly sour/tart finish. There is a very light sweetness with soft, creamy feel that is not cloying or heavy. None of the flavours or aromas stand out, making for a light refreshing beer with a moderate alcohol level usually hovering around the 5% ABV mark. Wit beers are usually quite cloudy from starch haze, with a very light straw to light golden colour. It’s a refreshing beer for hot summer days (or even horrible winter ones!)

Arguably the most popular commercial version of this beer is Hoegaarden, named after the village near Tienen in Flanders, which was the modern birthplace of witbier. Records of brewing in the village date back to 1445, when the local monks were enthusiastic brewers, but the tradition died out in the 1950s as consumer tastes moved towards different styles.

Ten years later, Pierre Celis, a milkman who had grown up next to the brewery and sometimes helped with brewing, decided to try to revive the style. He started a new brewery, called de Sluis, in his hay loft. He used the traditional ingredients of water, yeast, wheat, hops, coriander seed, and dried bitter (Curaçao) orange peel. In the 1980s, with demand for the product continuing to grow, Celis bought a former lemonade factory, to expand his brewing operations.

Things changed after a fire in 1985. As is traditional in Belgium, several brewers offered their help to keep the business going and Interbrew (now InBev) lent money for the purchase of other buildings to rebuild the brewery. Over time, Celis felt very strongly that the company used the loan to pressure him to change the recipe to make the beer more “mass market”. So Celis decided to sell them the brewery and moved to the United States where he set up the Celis Brewery in Austin, Texas, to continue making witbier to what he described as the ‘original’ Hoegaarden recipe. It was later acquired by Miller Brewing who eventually closed the brewery and sold the equipment and brand names.

THE INGREDIENTS

Most Witbier recipes will call for crushed coriander seed along with the zest of fresh (or dried) oranges. I find that much of the spicy flavour behind a Belgian Wit already comes from the yeast (White Labs WLP400 Belgian Wit Ale or Wyeast 3944 Belgian Witbier) so I will often completely leave out the coriander and orange peel. Try it either way and see which you prefer. You can also use sweet dried orange peel, which is what I have used in this brew. Some witbier recipes will also call for chamomile flowers as a reportedly “secret” ingredient that Celis used in the original Hoegaarden recipe. He debunked this in later interviews, indicating that coriander and bitter orange peel was all that he ever used.

As well as the more usual Pilsner malted barley malt found in this beer, I used flaked oats and flaked wheat (both unmalted). I did a short cereal mash at 50C to help the flaked grains along. A cereal mash step is used with unmalted or low enzyme grains such as rice, corn or oats to gelatinise the sugars before continuing with a traditional mash. To avoid a possible stuck mash with all the flaked grains, I used some rice hulls to help break-up the grain bed and allow the mash liquor to properly circulate during the mashing process. Flaked wheat and oats do not have a husk, so the natural filter bed in the Mash/Lauter Tun is greatly reduced. Brewers with systems that are prone to stuck sparges should add rice hulls at a rate of about 20:1 wheat to rice hull ratio to avoid stuck sparges.

THE BREWING

A pretty standard BM brew really, but I used a new Bacbrewing top extender filter with a cross tension piece of my own making. The Bacbrewing plates are supposed to be used with the supplied wing nut on its own, but I found that this did not clamp the plate tight enough to prevent grain seepage out of the malt tube. So I used my cross piece with the wing nut. This worked perfectly.

Recipe Specifications

Boil Size: 55.77 L

Post Boil Volume: 50.52 L

Batch Size (fermenter): 45.00 L

Bottling Volume: 43.00 L

Estimated OG: 1.057 SG

Estimated Colour: 6.8 EBC

Estimated IBU: 15.7 IBUs

Brewhouse Efficiency: 70.00 %

Est Mash Efficiency: 75.4 %

Boil Time: 90 Minutes

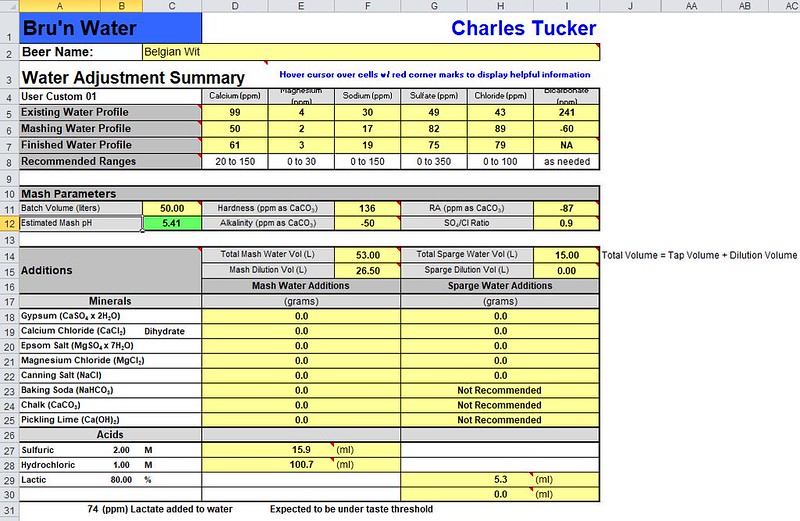

Water and treatment

75.0 L Thames Water tap water

18.5 L RO Water (from the Kingfisher’s Aquarium in Beckenham and used to dilute the tap water mineralisation)

500.0 mg Potassium metabisulphite (adding to the bulk water to remove chlorine and chloramines)

13.0 ml Lactic Acid 80% (used in sparge water only)

80.0 ml Hydrochloric acid 1M (used in mash liquor)

13.0 ml Sulphuric acid 2M (used in mash liquor)

Ingredients:

0.6 kg Rice Hulls (0.EBC) 5.0%

5.0 kg Wheat, Flaked, Unmalted (4.EBC) 41.3%

5.5 kg Pilsner (Weyermann) (3.3 EBC) 20.7%

0.5 kg Oats, Flaked (Instant/Ready Oats) (3.EBC) 4.1%

0.5 kg Brewing Sugar (Dextrose) (0.EBC) 4.1%

100.0 g Hallertauer Hersbrucker hop pellets 3% Alpha (Boil 60 mins) 15.7 IBUs

100.0 g Dried Orange Peel, Sweet (Boil 5.mins)

30.0 g Crushed Coriander Seed (Boil 5.mins)

0.5 Items Protafloc Tablet (Boil 15.mins)

1 tsp Yeast Nutrient WLN100 (Boil 10 mins)

4 packets Belgian Wit Ale yeast (White Labs #WLP400)

Mash Schedule:

Total Grain Weight: 12.1 kg

Mash In: Add 52.87 L of water 50C 15 min

Mash Step: Heat to 68C for 90 min

Mash Out: Heat to 76C for 10 min

Sparge: Fly sparge with 15.00 L water at 76.C

Brewing Notes:

Water treated with brewing salts to: Ca=50, Mg=10, Na=16, Cl=70, S04=7

(Hit minimums on Ca and Mg, keep the Cl:SO4 ratio low and equal).

Mash liquor pH no grain after acids was 2.98. Sparge pH was 5.3.

Mash pH at 68C was 5.68, then 5.47 after 4mins.

pH in boil kettle was 5.47. Post boil volume in kettle was 54L.

48L into fermenter at pH 5.3.

Cool wort to 20C and aerate well. Wort was aerated with pure oxygen using a wand for 60 secs at 1L pm flow.

Start fermentation at 20C and raise to 23C for the last third of fermentation.

Now for some pictures of the brewing underway

Summary of water additions using the Bru’n Water app:

A video of my grain mill in action:

Pilsner milling

The flaked oats and flaked wheat:

“Mosaic” shot of the grains before going into malt tube:

Unfortunately, at my age, a few aids are needed to help get the grains in the malt tube!:

Malt tube top filter in place:

And a video of the top plate performance showing the mash recirculation just starting to rise:

BAC top filter with my spreader

Mash pH:

Hops, ground coriander and sweet orange peel ready for the boil:

Final appearance of beer as it went into fermenter. Looks just the right colour and cloudiness:

Package as you would normally. I rack to 19 L Cornelius kegs that have first been purged with CO2. I chill the kegs to near freezing while carbonating at the same time in a keg conditioning fridge. After about 1-2 weeks at serving pressure the kegs will be carbonated and ready to serve. If you are in a hurry to drink it, this beer is best served fresh, so raise the CO2 pressure temporarily to 30-40 PSI to carbonate fast over a 24 period, and then turn back down to serving pressure. Carbonate this beer to higher than normal levels, around 2.5 to 3.0 volumes of CO2.